Vitamin D: The Hormone of Light That Regulates Thousands of Processes in the Body

There is something almost poetic about the fact that one of the most powerful hormones in the human body is created when light touches the skin. Vitamin D — or more precisely, the hormonal system hidden behind that name — was long considered merely a “bone vitamin.” Only in recent years has science begun to uncover the true breadth of its influence, revealing a picture that is far more complex and fascinating.

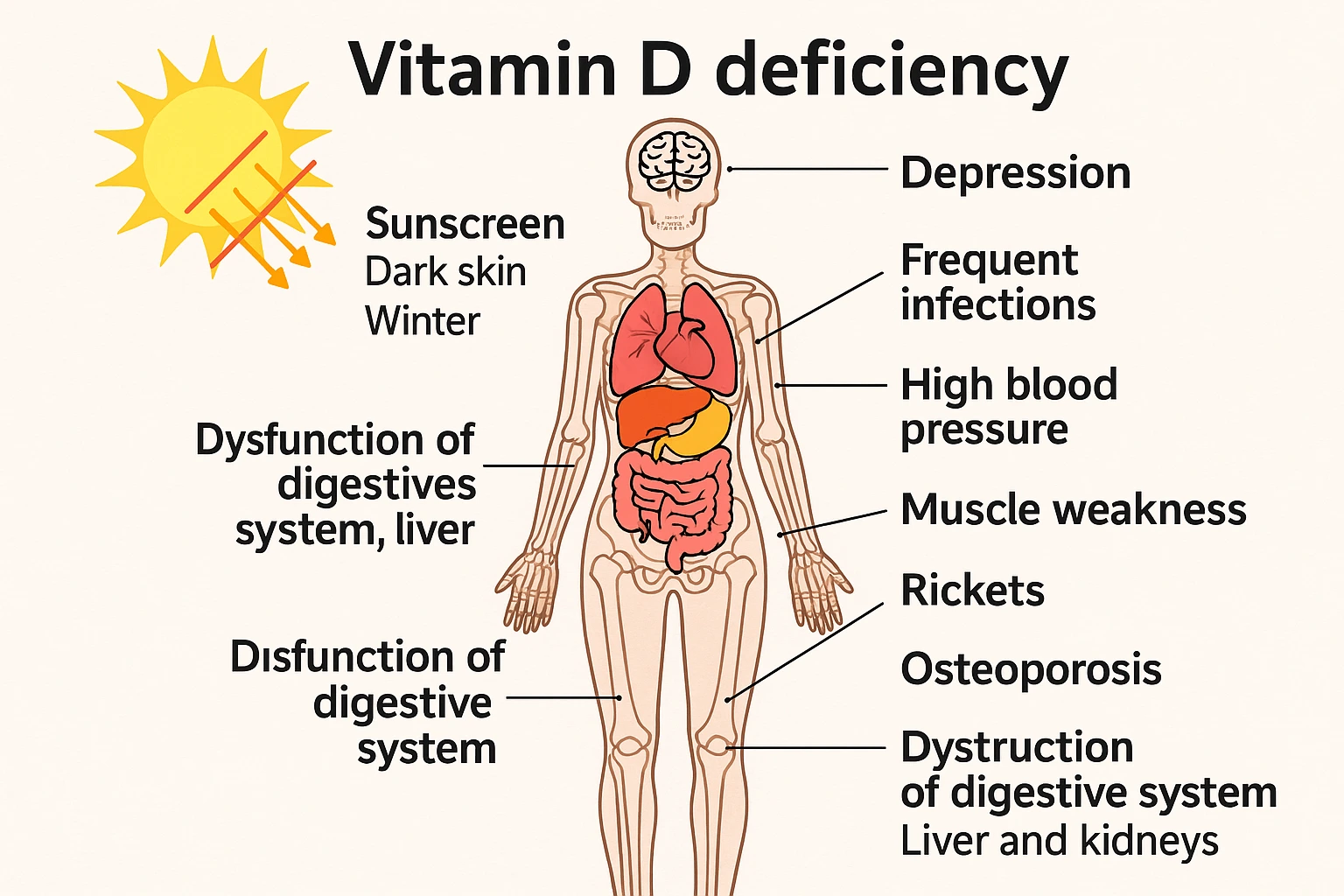

Vitamin D is not an ordinary micronutrient. It is a signaling molecule that regulates over a thousand genes, including those involved in immune responses, inflammation, muscle function, brain activity, and metabolism. When levels are insufficient — which is now the case for the majority of people — the body enters a quiet energy-conservation mode, often unnoticed in the short term, but highly significant over time.

What Is Vitamin D, Really?

Simply put, vitamin D is a hormone that is produced only when sunlight interacts with the skin. From that moment, a cascade of transformations begins: the skin produces cholecalciferol (D3), which travels to the liver and becomes calcidiol — the form measured in blood tests. Only in the kidneys is it converted into calcitriol, the active form that enters cells and “switches on” genes.

This means that a blood vitamin D level is not just a number. It reflects how well the body can regulate immunity, absorb calcium, maintain muscle strength, and support clear brain function.

Why Are Most People Deficient?

Despite medical progress, we live in an era where we spend more time indoors than ever before. Modern life has moved us from fields and courtyards into offices, schools, shopping centers, and apartments. Skin is covered by clothing, time is spent in front of screens rather than windows, and sunlight exposure is often brief — and frequently blocked by SPF that prevents vitamin D synthesis.

Add to this the fact that darker skin requires more sunlight, that European winters provide little to no UVB radiation, and that fatty fish is increasingly rare in everyday diets — and the conclusion becomes clear:

Vitamin D deficiency is no longer an exception. It is a global norm.

In older adults, the situation is even more pronounced: the skin produces less D3, time outdoors decreases, and diets often become less nutrient-dense. People with intestinal, liver, or kidney conditions may also struggle to activate vitamin D properly, even if intake appears sufficient.

What Does Vitamin D Do in the Body?

The most well-known role of vitamin D involves calcium regulation and bone health. But that is only the surface. In reality, vitamin D:

- Calms excessive inflammation, a key driver of chronic disease

- Improves muscle contraction and coordination

- Supports neuroprotection, preserving neuronal connections

- Activates and directs immune cells, almost like a commander

In practice, people with low vitamin D often notice vague but persistent symptoms: reduced energy, more frequent colds, slower recovery, poorer concentration, and a general sense of physical heaviness. These are not dramatic — but they are consistent.

How Can You Recognize a Deficiency?

The greatest challenge with vitamin D is that deficiency does not hurt. It does not send urgent signals and rarely presents as an acute problem. It is often discovered incidentally. Only in more severe deficits do symptoms such as the following appear:

- diffuse muscle weakness

- increased fatigue

- bone pain

- slower recovery

In children, deficiency can cause rickets; in adults, osteomalacia — a condition where bones lose strength due to poor mineralization.

How Much Vitamin D Does the Body Actually Need?

Standard recommendations often suggest around 600 IU per day, but many experts argue that this is sufficient only to prevent rickets — not to optimize health. As a result, many professional organizations now recommend 1,500 to 2,000 IU daily, especially during winter months.

The key principle is simple:

Dosage is individual — but blood levels between 30 and 50 ng/mL are generally considered optimal.

Levels below 20 ng/mL indicate deficiency.

Sunlight, Food, or Supplements?

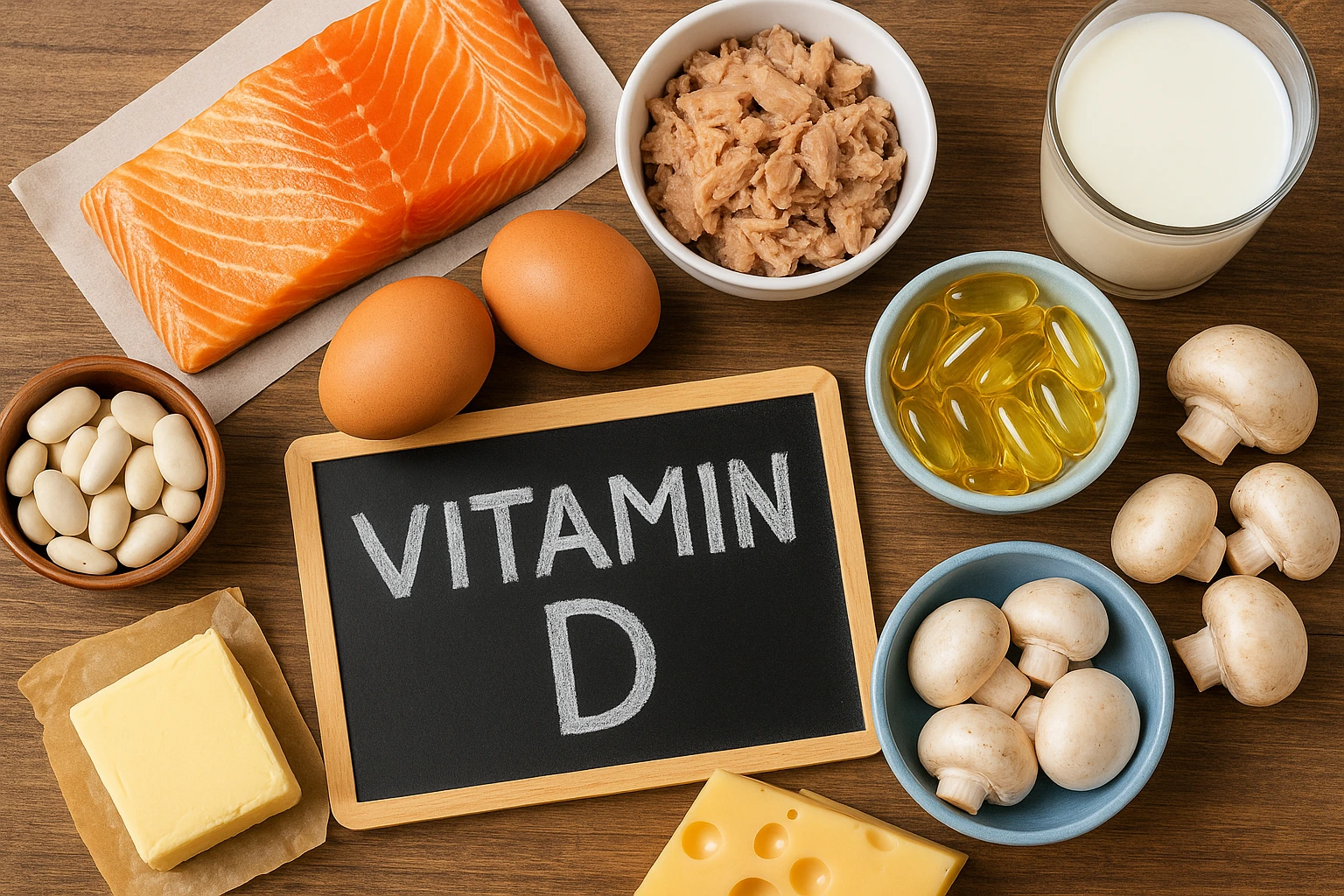

Sunlight remains the most powerful source of vitamin D.

Fifteen to thirty minutes of exposure several times per week can significantly raise levels — but only if UVB rays reach the skin. During winter, this is simply not possible in most European countries.

Food is the second source, but in practice provides only 10–20% of total needs. Fatty fish, egg yolks, and cod liver oil contain vitamin D, but they appear infrequently on modern menus.

For this reason, supplements are often the only realistic option, especially in winter. The most commonly recommended form is vitamin D3, which is more efficiently utilized by the body.

Can Vitamin D Be Harmful?

Yes — but only through excessive supplementation, not through sunlight or food.

Because vitamin D is fat-soluble, very high doses can raise blood calcium levels. Early signs include:

- nausea

- excessive thirst

- loss of appetite

In more severe cases, kidney strain may occur. Problems most often arise when weekly doses are mistakenly taken every day.

Research Notes: How I Personally Experienced Vitamin D

Vitamin D is an unusual supplement — it does the opposite of what many people expect.

It doesn’t provide a “boost,” it doesn’t speed up thoughts, and it doesn’t create a noticeable sensation that convinces you it’s working.

When I took it consistently, nothing dramatic happened. But slowly, day by day, I noticed a quiet sense of balance: less winter fatigue, a steadier energy rhythm, fewer sudden mood dips.

And only when I stopped did I truly notice what it had been doing.

A subtle heaviness returned, early afternoon fatigue crept back in, stress tolerance dropped, and focus felt slightly “foggy.” That’s when I realized vitamin D is not there to lift you up — but to prevent you from sinking.

That may be the quietest, yet most honest, measure of its effect.

Conclusion

Vitamin D is far more than a vitamin. It is a hormonal conductor that orchestrates immunity, brain function, muscles, and metabolism. When levels are insufficient, the body does not protest loudly — but the consequences accumulate slowly and silently.

Adequate vitamin D does not guarantee perfect health, but it creates a foundation of stability without which optimal function is difficult to achieve.

📚 Recommended Resources

Examine.com – Vitamin D

NIH – Vitamin D Fact Sheet

Harvard – Vitamin D Overview

Endocrine Society – Clinical Guidelines

🔗 Related Articles on Reviewetics

- Vitamin D and Omega-3: Similarities, Differences, and When to Combine Them

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: A Complete Guide to Benefits, Dosage, and Risks

- Magnesium: How It Works, Who Really Needs It, and When It Can Be Dangerous

This article is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not medical advice and does not replace professional diagnosis or treatment. If you have a medical condition or take medication, consult a healthcare professional before using dietary supplements.